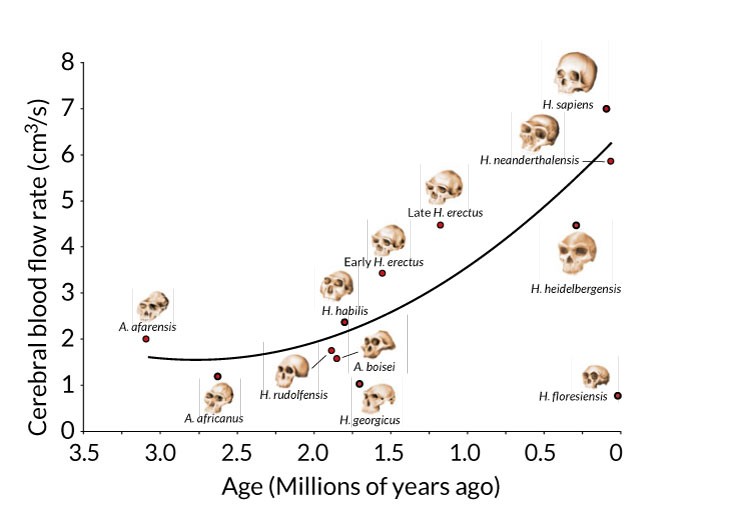

A groundbreaking study has revealed that modern humans and their recent relatives, including Neanderthals, experienced more rapid brain growth compared to earlier species in human evolution.

The research, conducted by scientists from the Universities of Reading, Oxford and Durham, challenges previous assumptions about how human brains evolved over time. Rather than occurring in sudden jumps between species, brain size increased gradually within each ancient human species.

By analyzing the largest-ever collection of ancient human fossils spanning 7 million years, researchers employed advanced computational methods to fill gaps in the fossil record, providing the most detailed picture yet of brain evolution.

"This study completely changes our understanding of how human brains evolved," explains Professor Chris Venditti from the University of Reading. "Rather than dramatic upgrades between species, we see steady, incremental changes happening within each species over millions of years."

The findings overturn previous beliefs that certain species, like Neanderthals, were static and unable to adapt. Instead, the research highlights continuous change as the key factor in brain size evolution.

The team discovered an intriguing pattern - while larger-bodied species typically had bigger brains, variations within individual species did not consistently align with body size. This suggests that different factors influenced brain development patterns across extended time periods versus within single species.

Dr Joanna Baker from the University of Reading notes that understanding why and how humans developed large brains remains central to human evolution research. The study demonstrates that our distinctive large brains emerged primarily through gradual modifications within individual species over time.

This research stems from a £1 million Leverhulme Trust grant aimed at better understanding human ancestor evolution, marking a major shift in our knowledge of how human brains developed through history.