A groundbreaking study from Dutch researchers has uncovered why attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, and dyscalculia frequently appear together in children. The research shows these conditions share common genetic foundations, explaining why children with ADHD often experience challenges with reading, spelling, and mathematics.

The extensive study, conducted by researchers at the University of Amsterdam and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, analyzed data from over 19,000 twins to investigate the relationship between these conditions. Their findings challenge the common assumption that one condition directly causes another.

"Many assume that one condition causes the other. For example, children with learning difficulties may struggle to follow class instructions, potentially leading to ADHD symptoms," explained study author Elsje van Bergen from Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. "However, our research reveals a different story."

The study found that children with ADHD were approximately 2.7 times more likely to have dyslexia and 2.1 times more likely to have dyscalculia compared to children without ADHD. About 37% of children who met ADHD criteria also showed signs of dyslexia or dyscalculia.

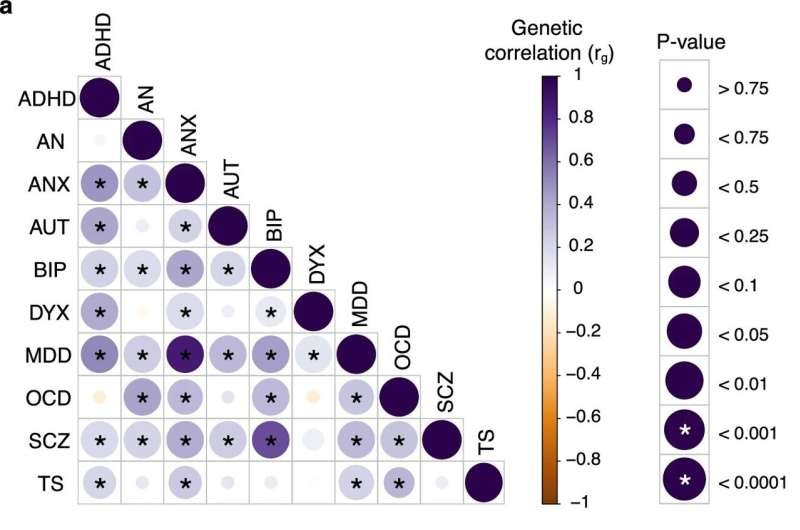

Through detailed statistical analysis of twin data, researchers discovered that genetic factors increasing ADHD risk overlap with those increasing risk for dyslexia and dyscalculia. This shared genetic predisposition means individuals can inherit variations making them susceptible to multiple conditions. A groundbreaking study by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics has uncovered new insights into how genetic variants associated with dyslexia affect brain structure and function.

The research indicates that learning problems in children with ADHD aren't simply caused by attention difficulties, but reflect a shared genetic vulnerability affecting both attention and learning abilities. This finding has implications for treatment approaches.

"Our findings suggest that treating ADHD alone won't necessarily improve academic skills, and vice versa," van Bergen noted. "Each condition requires targeted support."

The study emphasizes that while genetics plays a major role, environmental factors remain important. Early interventions and quality teaching can make substantial differences in outcomes for affected children.

These insights could lead to more effective, personalized support strategies for children with these conditions, helping educators and healthcare providers better understand and address their unique needs.